|

Symphony

MONUMENTAL MAHLER 5TH IN SO CO PHIL'S SEASON ENDING CONCERT

by Terry McNeill

Sunday, April 14, 2024

Chamber

OAKMONT SEASON CLOSES WITH STRAUSS' PASSIONATE SONATA

by Terry McNeill

Thursday, April 11, 2024

Chamber

MORE GOLD THAN KORN AT ALEXANDER SQ CONCERT

by Terry McNeill

Sunday, April 7, 2024

Choral and Vocal

VIBRANT GOOD FRIDAY REQUIEM AT CHURCH OF THE ROSES

by Pamela Hicks Gailey

Friday, March 29, 2024

TWO OLD, TWO NEW AT THE SR SYMPHONY'S MARCH CONCERT IN WEILL

by Peter Lert

Saturday, March 23, 2024

Chamber

NOT A SEVENTH BUT A FIRST AT SPRING LAKE VILLAGE CONCERT

by Terry McNeill

Wednesday, March 20, 2024

THIRTY-THREE PLUS VARIATIONS AND AN OCEAN VIEW

by Terry McNeill

Saturday, March 16, 2024

Choral and Vocal

A ST. JOHN PASSION FOR THE AGES

by Abby Wasserman

Friday, March 8, 2024

Choral and Vocal

SPLENDID SCHUBERT SONGS IN SANET ALLEN RECITAL

by Terry McNeill

Saturday, March 2, 2024

Chamber

SHAW'S MICROFICTIONS HIGHLIGHTS MIRO QUARTET'S SEBASTOPOL CONCERT

by Peter Lert

Friday, March 1, 2024

|

|

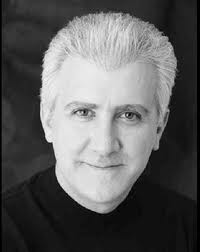

Conductor Gabriel Sakakeeny |

STERLING BEETHOVEN AND CHAUSSON IN FINAL SAKAKEENY AMERICAN PHIL CONCERTS AT WELLS

by Candace N. English

Sunday, February 20, 2011

As classical music events go, the atmosphere of an American Philharmonic Sonoma County concert seems casual, but the performances Feb. 19 and 20 at the Wells Center were anything but. The orchestra's recent 12-day tour of China has clearly congealed the group into a body of musicians capable of reaching heretofore unattainable heights of musicianship and beauty.

Philharmonic concerts, being community oriented, always begin with greetings and comments by conductor Gabriel Sakakeeny, which means that the orchestra comes on stage and sits quietly for some length of time before the first downbeat finally arrives. Their ability to launch into a stirring overture, after this apparent lull, has always been impressive to me, and this occasion was no exception

The program began with the Brahms Tragic Overture, Op. 81, composed in 1880. This work is an example of the composer's extraordinary command of traditional form and orchestration, yet at the same time it illustrates his experimentation with sonata form and clear intent to ellicit strong emotions. This work, dark and beautifully crafted, begins with a grand tutti as the first of three distinct themes is introduced. Soon things quiet down a bit and we hear the second theme, played here to perfection by oboist Chris Krive. The horns barely allude to the third theme before it is taken up by the violins, and without further ado the ingenious development is underway. I saw myself at a great loom, weaving themes. I imagined the mingling of different colors and textures, woven and blended together in a fine tapestry, until a brilliant tympani moment, played by Tony Blake, brought me back into the hall, wondering what will happen next.

Surprisingly, here the tympani do not herald the recapitulation, as is often the case, but return us to the loom, for more dark weavings, until the first theme finally reemerges with stunning clarity and we are propelled into the dramatic and turbulent coda. Its forward momentum is stalled briefly by woodwinds who seem to be asking, "Shall we add a bit more red, or black, before tying off?" Writers have called this work somber, grim, the coda a "final disaster". To me, its impression is not all that tragic, but surely brilliant and ultimately victorious.

Mr. Sakakeeny introduced the second work, Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, by putting the piece in historical context and pointing out special moments to listen for. Composed in 1894 and based on a poem by Mallarm�, the clearly programmatic nature is characterized by lust and animism. The opening flute solo, so poignant and familiar but too often rendered with a large portion of schmaltz, was played with delicate beauty and purity by Debra Ortega. The musical material of the Prelude could be characterized not as themes but rather as scenes, freely evoking the sensuality of the Mallarm� poem. The music sounded almost improvisational, foreshadowing the future of symphonic music with its use of whole tone scales, forbidden tri-tones, unusual voicings, tone clusters and washes, all with mixed and alternating meters that transport us out of musical time as we thought we knew it. The conductor's fluid and graceful baton underscored the rhythmic infrastructure of this work. This seminal work was choreographed by Nijinsky, praised by Boulez as the awakening of modern music and even said to be Michael Jackson's "favorite song." Having attended or played in every American Philharmonic program for the last six years, it seems the orchestra has never sounded better than when playing this profound and complicated music. The experience was completely transcendent.

Ernst Chausson is an interesting, lesser-known composer, who was born and lived in Paris during the latter half of the 19th Century. Coming from a well-to-do family, he became a barrister in the Paris Court of Appeals before deciding on a musical career, studying with Massenet. Of his approximately 60 works, the overwhelming majority feature the voice singing lyrical poetry. Chausson's Poeme is the exception to the rule, because instead of being sung and based on a poem, it is a poem, a beautiful and expansive musical poem for violin and orchestra. Violinist Solenne Seguillon, born in France, performed the solo part. To describe her playing as �poetry in motion� might sound like a clich�. Her performance of this work, part of the standard violin repertoire, revealed a great depth of feeling and understanding of the intricate material. Her technique, though not flawless, was well suited to the Chausson. Ms. Seguillon's extraordinary musicality and gorgeous tone were everywhere evident.

After intermission, Congressperson Lynn Woolsey spoke emphasizing the need for art and music education, and there were presentations honoring the 12 years of Mr. Sakakeeny's leadership. Again, the orchestra sat for long minutes, this time waiting for the empty downbeat of one of the most famous works in the symphonic repertoire, Beethoven's C Minor Symphony, Op. 67. To think that this work was composed over at least four years time by a man who was going deaf, and who probably never heard his masterwork performed, fills me with compassion. The rigors and complexity of Beethoven's Fifth, an arduous effort for both orchestra and conductor, were handled admirably by the Philharmonic. Mr. Sakakeeny and the orchestra were in high gear, commanding and driving the giant tutti sections, executing the more transparent moments with finesse and inspiration. There were minor imperfections at times, and holding this Symphony together is no small feat, but the excitement never waned. The pathos, commitment, inspiration and sheer grit of this performance was a memorable experience. The violins were not numerous enough to make a strong impression but the precision and power of the lower strings, especially in the last movement, exceeded anything I've ever heard from this orchestra. When it was over, the final chord dying away, there lingered in the hall a rare sense of validation, accomplishment and solidarity shared by orchestra and audience alike.

These concerts were said to have been the last for which Mr. Sakakeeny will be the regular conductor. He will stay on for a time in the role of musical director, helping to lead the orchestra into its next phase of development. Noting the current penchant of American orchestras for leadership by conductors who are foreign nationals, one can ask rhetorically why he has not received greater recognition with guest appearances and recording opportunities.

|