|

Symphony

FROM THE NEW WORLD TO THE OLD WORLD

by Peter Lert

Saturday, June 14, 2025

Chamber

MC2 DUO RECITAL CLOSES 222'S SEASON

by Terry McNeill

Saturday, June 14, 2025

Choral and Vocal

CANTIAMO SONOMA'S LUSCIOUS A CAPELLA SINGING IN SEASON ENDING CONCERT

by Pamela Hicks Gailey

Sunday, June 8, 2025

Symphony

SRS SEASON ENDS WITH RESOUNDING TA-TA-TA-BANG

by Terry McNeill

Sunday, June 1, 2025

Symphony

YOUTHFUL VIRTUOSITY ON DISPLAY AT USO'S MAY CONCERTS

by Peter Lert

Saturday, May 17, 2025

Symphony

MYSTICAL PLANETS AND LIVELY GERSHWIN ORTIZ AT FINAL SRS CONCERT

by Peter Lert

Sunday, May 4, 2025

Symphony

VSO'S CONCERT MUSIC OF TIME, MUSIC OF PLACE

by Peter Lert

Sunday, April 27, 2025

VOCAL ELEGANCE AND FIRE AT THE 222'S RECITAL APRIL 26

by Pamela Hicks Gailey

Saturday, April 26, 2025

CANTIAMO SONOMA SINGS AN INSPIRED GOOD FRIDAY MOZART REQUIEM CONCERT

by Pamela Hicks Gailey

Friday, April 18, 2025

DRAMATIC SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY CLOSES PHILHARMONIC'S 25TH SEASON

by Terry McNeill

Sunday, April 13, 2025

|

|

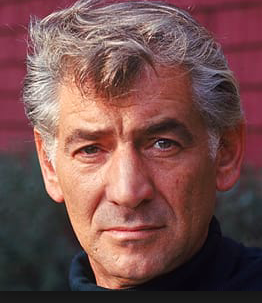

Composer Leonard Bernstein |

PEACE AND LOVE FROM THE SANTA ROSA SYMPHONY

by Steve Osborn

Sunday, November 4, 2018

Before the Santa Rosa Symphony’s Nov. 4 performance of Leonard Bernstein’s “Symphonic Dances from West Side Story,” Symphony CEO Alan Silow took a moment to acknowledge the victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue attack and to observe that music offers a more peaceful and loving view of the world.

Mr. Silow’s comments were timely, and the Symphony proved them to be true with an energetic and memorable performance of Bernstein’s dances, along with an eclectic program that ranged from Liszt’s “Mephisto Waltz No. 1,” Kodaly’s “Dances of Galanta” and Villa Lobos’ guitar concerto, with soloist Sharon Isbin.

For sheer audacity and panache, the Symphony’s show-closing performance of “West Side Story” easily eclipsed the other offerings. The musicians played at full tilt and with masterful precision, aided greatly by Conductor Francesco Lecce-Chong’s lucid direction and forward momentum. The black-clad, mostly middle-aged orchestra showed that it can really swing, especially when backed by a torrid percussion section.

From the opening finger snaps, Bernstein’s dances were all rhythm, almost all the time. The “Mambo” dance really cooked, with the intricate orchestration producing a joyous and irresistible noise. Equally joyous was the “Cool Fugue,” with its crisp lines and outstanding drum-set pyrotechnics. The slower “Somewhere” dance was less successful, a victim of its own schmaltzy melody. In contrast, the slow “Finale” eased up on the schmaltz and offered a somber reflection on the preceding “Rumble,” a searing depiction of a deadly fight. Throughout the performance, the players showed commendable versatility, producing solid sound at tempos that ranged from vivace to presto to hyperdrive. Stray notes were absent from even the fastest passages, and everyone started, stopped, swelled and diminished on cue.

Considerably more languid musical forms inhabited the Villa-Lobos guitar concerto, which concluded the first half of the concert. The concerto drifted from one musical idea to the next without much of an overarching structure. Adding to the murk was Ms. Isbin’s insouciant playing of her amplified instrument. The debate over amplifying classical guitars for concertos continues to rage, but it’s worth noting that Andres Segovia, the Spanish virtuoso for whom Villa-Lobos wrote this particular concerto, was a staunch opponent of amplification.

Setting aside Weill Hall’s superb acoustics, it’s hard to imagine that a sound as harsh and artificial as the one emanating from Ms. Isbin’s amplifier had anything to do with Villa-Lobos’ conception for the concerto. The bass dominated the amplifier, at times drowning out runs on the upper strings. Notes that should have rung out were muted by an electronic haze.

Ms. Isbin could have salvaged the sound by playing more passionately and expressively, but her face remained buried in her score, and she didn’t make much effort to connect with the audience. Nonetheless, she did play an encore, Granados’ famous Spanish dance, a staple of classical radio stations. With no competing orchestra, there was even less need for amplification, but she plugged in once again, with similar results.

The program opened with a lively reading of Kodaly’s “Dances of Galanta,” a suite of 18th-century Hungarian gypsy dances that were originally intended to entice recruits into that era’s endless wars. The intent may have been militaristic, but the dances are benign and tuneful, falling gracefully into Kodaly’s inventive orchestration. Soloists abounded, but the standout was principal clarinetist Roy Zajac, who imbued his tunes with an authentic gypsy feel. The work opened a bit slowly, but the inevitable accelerando to a whirling close was well controlled and effective.

The opener for the second half was yet another dance, this time Liszt’s much-played “Mephisto Waltz No. 1.” Mr. Lecce-Chong began the dance with ferocious energy, leading the cellos in an impressive series of down-bows to punch out the eerie melody. The dynamic control was spot-on for the rest of the piece, and the frenzy was palpable.

“West Side Story” followed, and then an unexpected encore where about a dozen members of the symphony’s Youth Orchestra joined their older compatriots in a vivacious performance of Bernstein’s “Candide” overture. One diminutive second violinist barely reached the top of her music stand, but the rest seemed to be high schoolers, and they all played admirably.

Reprinted by permission from San Francisco Classical Voice.

|