|

Symphony

FROM THE NEW WORLD TO THE OLD WORLD

by Peter Lert

Saturday, June 14, 2025

Chamber

MC2 DUO RECITAL CLOSES 222'S SEASON

by Terry McNeill

Saturday, June 14, 2025

Choral and Vocal

CANTIAMO SONOMA'S LUSCIOUS A CAPELLA SINGING IN SEASON ENDING CONCERT

by Pamela Hicks Gailey

Sunday, June 8, 2025

Symphony

SRS SEASON ENDS WITH RESOUNDING TA-TA-TA-BANG

by Terry McNeill

Sunday, June 1, 2025

Symphony

YOUTHFUL VIRTUOSITY ON DISPLAY AT USO'S MAY CONCERTS

by Peter Lert

Saturday, May 17, 2025

Symphony

MYSTICAL PLANETS AND LIVELY GERSHWIN ORTIZ AT FINAL SRS CONCERT

by Peter Lert

Sunday, May 4, 2025

Symphony

VSO'S CONCERT MUSIC OF TIME, MUSIC OF PLACE

by Peter Lert

Sunday, April 27, 2025

VOCAL ELEGANCE AND FIRE AT THE 222'S RECITAL APRIL 26

by Pamela Hicks Gailey

Saturday, April 26, 2025

CANTIAMO SONOMA SINGS AN INSPIRED GOOD FRIDAY MOZART REQUIEM CONCERT

by Pamela Hicks Gailey

Friday, April 18, 2025

DRAMATIC SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY CLOSES PHILHARMONIC'S 25TH SEASON

by Terry McNeill

Sunday, April 13, 2025

|

|

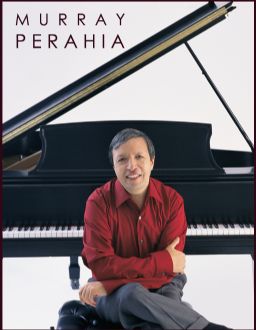

TRANSCENDENT ARTISTRY FROM MURRAY PERAHIA

by Steve Osborn

Thursday, March 19, 2009

In his March 19 recital at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley, pianist Murray Perahia played the three Bs — Bach, Beethoven and Brahms — with a Schubert encore at the end supplying the plural S. His program ranged from the high Baroque (Bach’s Partita No. 6 in E minor) to the late Classical (Beethoven’s “Pastorale” Sonata, Op. 28) to the full-blown Romantic (Brahms’s “Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel,” a work that embodies the radical transformation of musical style from the 18th to 19th centuries).

For listeners craving an evening of traditional classical music, this recital had it all: masterpieces played by one of the world’s greatest pianists in a convivial setting. The house was full to overflowing.

Perahia received a hero’s welcome as he strode on stage, fully decked in tails. He settled into the piano bench, draped the tails behind him, and set right to work on the opening Toccata of the Bach, the first of seven movements. At first, his playing was restrained, almost quiescent, as he gathered the various musical threads together before the entrance of the theme. His face was etched in a frown, and he kept a close eye on his hands.

Little by little, he began to increase the volume and to sway, giving the movement a narrative arch. That narrative continued in the subsequent Allemande, which was marked by clarity of tone and delicacy of attack. Then came the highly rhythmic Courante. Here the syncopations were perfect, the rapid right-hand runs flawless, the left-hand arpeggios a movement in themselves. The unflagging beat continued through the remaining movements, with Perahia repeatedly using his upper body to punctuate the rhythm.

Perahia’s finger work was dazzling throughout, but his sense of rhythm and forward motion are what made the performance so memorable. By the concluding Gigue, he was positively rollicking, his jowls shaking as he emphatically repeated the insistent two-note figure that brings the Partita to a close. During the thunderous applause, the man to my left leaned over and said, out of the blue, “You can hear every single note when he plays — he doesn’t gloss over anything.”

Beethoven’s “Pastorale” Sonata, with its traditional four-movement form, is generally considered the last work of his early, Classical period. That form is evident from the outset, with the twin themes of the opening movement, followed in turn by their development and recapitulation. Classic form makes for a classic story, and Perahia narrated this one superbly. Beginning with the repeated notes in the bass, he leaned into the keyboard and built strong dramatic tension, unfolding the opening theme at a stately pace. When he arrived at the second, the transition from major to minor seemed almost like an epiphany, as if Perahia were inhabiting Beethoven’s own thoughts.

The story got even better from there. In the Andante second movement, Perahia often lifted up his left hand, turned it over as if to examine his palm, and then expertly reset it on the keyboard, emphasizing the crucial bass line. Before playing the many descending figures with his right, he waited until the last possible nanosecond, ratcheting up the tension. That playfulness persisted in the Scherzo, where he seemed to barely touch the keys. In the final Rondo, he offered his loudest playing yet, giving full contrast to the sforzandos and pianissimos and creating enormous excitement with the sheer speed of his attack. He got up very slowly when he was done.

The exhausted audience got some relief during intermission, but Perahia had only begun. Brahms’s “Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel” does indeed have variations, but they’re really just a prelude to the main event: the thunderous Fugue at the end, which bears almost no stylistic resemblance to the original theme.

The piece begins innocently enough, with Handel’s somewhat tepid melody peeking out beneath a filigree of ornamentation. Perahia made the Steinway concert grand sound almost like a harpsichord as he deftly unveiled the material at hand. After an opening variation in the baroque style, the real Brahms began creeping in. By about the fourth variation (there are 25), the stentorian bass announced an entirely new musical language, far removed from Handel.

Perahia navigated the rapidly changing moods of the variations with ease. Many are quite short, and he proved equally adept at being assertive, limpid, agitated, and reflexive. All those moods and more were on display in the final fugue, where the music really takes off. Here he managed to make every entry of the four-note subject sound new and different. He rocked back and forth in his bench as if driving a team of horses, spurring each one to the max.

The standing ovation was instantaneous and unanimous. Perahia looked drained, but after four curtain calls, he sat down and played Schubert’s B-flat Impromptu as if he had not a care in the world. His sound was serene, his fingering impeccable, his artistry transcendent.

|